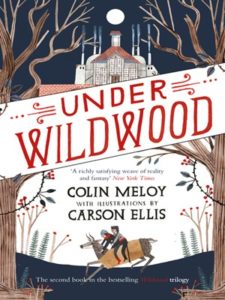

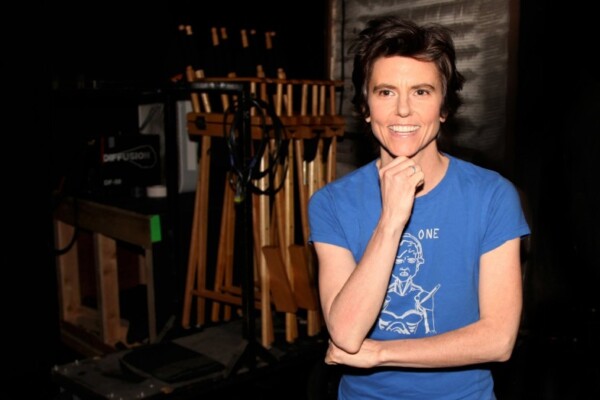

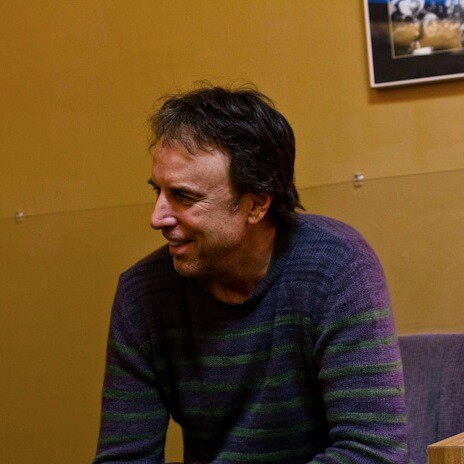

Timshel Matheny—currently a songwriter in the band Roman Candle—recently caught up with Colin Meloy and Carson Ellis, who were in Nashville on a book tour, supporting Meloy’s recent novel Under Wildwood.

Under Wildwood is the follow-up to Meloy’s highly acclaimed children’s fantasy novel, Wildwood. Both books were illustrated by Carson Ellis, who is an award-winning illustrator, as well as the artist behind all of The Decemberists’ album art (as well as tour posters, t-shirts, etc.).

“Drinks With†is an interview series started by Skip and Timshel Matheny in 2009. The interviews are almost always done in person and typically discuss the creative process. This interview is the part of a series for Paste of speaking with authors and visual artists.

Matheny: What’s your favorite drink?

Ellis: Well, I’m pregnant, so I can’t drink any booze, but if I wasn’t…I love whiskey and I love red wine.

Meloy: Yeah, I guess red wine is sort of my drink of choice. We really like kind of smoky, peppery, rhone wines.

Matheny: Do you have something special you go to when you are pregnant?

Ellis: Nooooo. I drink bubbly water with a lime in it, and it’s a bummer. I just drink it to stay hydrated and it’s more exciting than water that is not bubbly.

Matheny: When you were writing this book, what was your typical day like? I read that during the first book [Wildwood] you walked a bunch in [Portland’s] Forest Park while you were writing. There seem to be more industrial landscapes in Under Wildwood. Did you change your scenery for the second book? Tour the Shanghai Tunnels? I think you used to be able to go down in them for tours when I lived there.

Meloy: No [laughs]. I’ve done a couple tours though. We did a tour of the Shanghai Tunnels where it was the ghost-themed tour, and it was really, really hokey and over-the- top. And then a few years ago, The Portland Monthly magazine did an interview with me and the whole set-up like “Oh, we’ll interview you while you are getting a tour of the Shanghai Tunnels.†So, I went on a tour of the Shanghai Tunnels, but the guy kind of totally pulled the veil aside and kind of burst my bubble on the fact that the Shanghai tunnels aren’t really Shanghai Tunnels. They’re mostly just storage. And there is no evidence that they were ever used for Shanghaiing. But we did walk in the woods a lot. Not necessarily to get inspiration—but more so because walking is just good for the creative process. And getting out of your workspace and just kind of meandering, I think can free your mind up a lot if you are kind of locked up a bit. We’ve done that on both books.

Ellis: He would be like, “Let’s take a walk,†when he was feeling kind of stuck. Then he would sort of talk through the narrative. When he got stuck he would sort of think out loud, and I would walk and listen and give my two cents when required.

Meloy: Yeah. It was a daily walk. The writing on this was just sort of six to eight hours a day just sitting down and writing. Then getting done with the manuscript and giving it to Carson. Then Carson started working on the illustrations for six to eight hours a day.

Matheny: So during that time did you swap roles with family life? Was your little boy in school? Practically speaking, how did that work?

Meloy: Yeah, he was in school. It was his first year in kindergarten so that was helpful.

Ellis: But Colin worked weekends for a good couple of months. And then I worked weekends for a good couple of months—which was kind of a bummer because everyone would want to hang out on the weekends.

Meloy: But every day I had to meet a daily word-count quota. I mean, I only had four months to do it. Off and on. I had a chunk of it written by the time The Decembrists’ tour had finished in late August. And then I immediately started working on it. And I turned that in mid-February. So it was probably like five or six months. But close near the end I was working every day.

Matheny: Was that a self-imposed word count?

Meloy: Well, yeah, because I had to meet the deadline. I kind of knew how long it was gonna be, or I just guessed considering what was going on. It ended up being shorter than I thought it was. I kind of pared it down because it was gonna get too long. And also, I wasn’t going to meet the deadline. So I had to put some of the events that were going to happen in the end into the next book.

Matheny: Writing that much in that amount of time sounds like a lot of work, but you were still creating a fantastical story for young people. How did you strike a balance between the work of getting it done and the work of making things up? Was it difficult to keep up the discipline and still reserve a part of your brain that could be playful enough to write this kind of story?

Meloy: Well, it’s still making up stories for eight hours a day. It’s not like building television sets or anything like that. It’s still an enjoyable process. I don’t think that every single minute of that six to eight hours I was typing. I would have finished it in a week just based on my words per minute typing ability. There’s a lot of stepping away and surfing the web and playing guitar and, you know, things to break it up a little bit. I think my brain naturally wants to do things to make itself lighten up.

Matheny: Did you find a lot of the story unfolding as you wrote it ? Like J.R.R. Tolkien saying when he first wrote the character of Aragorn [into the Lord of the Rings], he had no idea this guy in a pub would become a great King, until he followed him through writing the story. Or was there more of a pre-existing idea for the full story when you began? I think J.K. Rowling famously made up the outline for all seven Harry Potter books on the back of a napkin, riding on a train. I imagine for her, writing out the books was filling in the details between plot moments she already knew would happen. When you were starting out, how much of the story did you already know?

Meloy: Yeah. I couldn’t just follow the characters. Because I knew I wanted it to have a more traditional structure, to read like a folk tale. And I knew it would have to have a concise ending. At least certainly the first one. And because it is an adventure story it just made more sense to me, to kind of plot it out. And to get all of the beats right, and the going back and forth between the different stories and the weaving of them together. It just made more sense to plot it out initially and then fill in the spaces.

Matheny: Were there any characters that were surprises to you once you had been writing them for 300 pages?

Meloy: Curtis, from the first story was kind of like that. I had already started writing it and initially I thought it was only going to be Prue going on this adventure. But I realized I couldn’t just have her [by herself] all the time from the moment her brother is kidnapped. She wouldn’t have anybody to talk to. So I put Curtis in there to give her a friend in that huge section. Then when they entered Wildwood, I was like, well, of course he should follow because then they can split apart and then, they are effectively two different kinds of tour guides of [Wildwood]. You can see what would happen if you made two different decisions, you know? And so in that sense, you can have a more dynamic feel of the world.

Matheny: As a musician and a songwriter I know a lot of the writing process can happen in the listening back. You might create a melody or a piece of music and by hearing it over and over again, more ideas or directions for that song are revealed. How did your relationship to listening and writing change for you as a writer of books, as opposed to a songwriter?

Meloy: One thing that I did discover with this book, which I hadn’t done with the previous book and I wish I had, when I finished, is I actually read it aloud to myself. I spent a week and sat down every day and read it aloud. Just listening for the rhythm of it. And you know, you are not only picking up typos and word repetitions, but it’s a really good way to edit. Also you can just feel the rhythm of the sentences and how they kind of fold into one another. And so I did that on this book and it was really helpful. It just took a really long time. Then I ended up doing the audio book for it too, so I had to do it all over again. So I have read that book aloud twice all the way through.

Matheny: [to Ellis] I have heard you say that as you were sitting down to illustrate for these novels, the Forest Park pictures were some of the hardest for you to capture. I think you were talking about the different shades of green in the park and how on your first illustrations, the greens actually turned out “too bright.†You said that you had to go back and not think about how you saw them but instead about how you felt them when you were inside of those woods. I thought that was a really lovely description of your process. Did that happen at other moments for you, when you were illustrating certain scenes? Did it matter that Forest Park is a place to which you have a strong personal connection?

Ellis: That’s the thing. Forest Park is just such a sentimental place to me and a place where I’ve spent tons of time. And also, visually, it’s just a really busy place. It’s like a jungle. And in addition to that, there’s a lot of atmospheric stuff that is going on and happening in a Forest Park Vista. There is rain, and there is mist and all of this stuff. I realized that I really didn’t know how to paint it in a way that would be naturalistic and recognizable as Forest Park. So I did just have to do something that felt more, I don’t know, emotionally representative.

Matheny: That sounds really tricky. It seems like because Forest Park is such a visually stimulating place that you’d have to let some of the details recede in order to get an essential idea across. How did you do it?

Ellis: Yeah, it was hard. And it was hard to let go of my own idea. But I also knew that this was a book set in the Pacific Northwest for people that didn’t necessarily live there. The book has such a regional aspect to it, and I wanted people to get that feeling of, “oh yeah, the Pacific Northwest. It’s all woods and mist and rain!†I wanted them to feel that when they looked at the illustrations. But I don’t know, in the case of Wildwood, I was looking at a lot of this particular of avant garde-ish Russian and Polish art. And I felt like [landscape painting] was something that those artists did really well—these sort of surrealist landscapes that definitely evoked a specific sort of wilderness or landscape without being literal at all. I was really inspired by it. I thought, “I could feel really good about doing that, and then, not have to be able to paint Forest Park.†Which is so hard [laughs]. I wanted to include all of those other details but in the end I just ended up doing what I felt like I knew how to do, you know? I think that’s all that we can ever do [laughs]—just follow our instincts and try to push ourselves into a realm that’s maybe a little bit out of our comfort zone, while still doing something that we feel like we know how to do.

Matheny: Did you find that by spending so much creative energy and focus on the book, that you stirred up other creative works, not related at all to the book? Songs or otherwise? One of our favorite stories is about the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke taking 10 years to finish his Duino Elegies, and once he had finally finished them, he unexpectedly started and finished an entirely separate work, Sonnets to Orpheus, in a few days. Do you find that working hard in one particular creative direction allows you to come up with other unexpected works?

Meloy: Yeah. That happens to me a lot in songwriting. Where I’ll feel so stopped up, and then write a song, and then all of the sudden two more will just sort of blossom out of that one song that are totally different. It’s weird how they often come in twos and threes. And I think that has so much to do with shaking things up. Also, confidence. All of the sudden, having this renewed confidence in what you can do. I feel like a lot of writer’s block has to do with just a lack of confidence or losing confidence or fear that it’s gone. When I was writing this book, when I think I was at my peak of productivity, when I was really working the most, I also started writing short stories, just on the side. I would spend half the day working on Wildwood and then all of the sudden just be moved to write some short stories that weren’t even part of the series or part of the thing. I just started writing them, all of the sudden because I had this, sort of, outpouring of creativity. So I think it’s true that it works that way.

Ellis: And also, your muscles are just so in shape when you are working all of the time. Those creative muscles.

Meloy: It doesn’t feel like it takes as much effort. My sister [novelist Maile Meloy] says that writing is a muscle and you just need to exercise it and keep it exercised.

Ellis: Yeah. And I think that, like with the case of Wildwood and Under Wildwood, the deadlines were really tight and the amount of work that needed to be done was so above and beyond what I would normally have to do in the course of three months—you know it was like 85 illustrations and only a handful of months to do them in—that as much as I love it, and I really do love it, I could also feel like I was imprisoned by my job some times. But it is not imprisoned by needing to have creative output. Which is one thing that I feel like is compulsively happening anyways. I always want to be drawing. But there’s just this creeping urge that builds and builds to draw something that you don’t have to [laughs], you know? Or work on something that isn’t on this 85 item to-do list. So, like when I would take a break once I had started working on the manuscript, I was also working on two different picture book manuscripts while I was illustrating this for the first time. It was like this thing that I had been wanting to do for 10 years, and I couldn’t get my head around how exactly to do it and then, somehow, in my sort of desperate need to get away from this one creative thing, I kind of dove right into the other. I was finally able to get over that hump.

Matheny: That makes sense.

Ellis: I definitely feel like both of us do that. We kind of procrastinate the creative work we have to do with other creative work we want to do. It’s just like all making stuff all of the time.

Matheny: That’s a good problem to have.

Ellis: Yeah, it totally is. I actually was obsessing over a record when I was working on these illustrations. I just couldn’t stop listening to it. And even though I didn’t have like an extra second in my schedule I wrote the musician’s people and was like, “Can I make a poster for you?†[all laughing] Cause I felt like it would have been the perfect for way to just kind of, you know, escape for a day.

Matheny: What record was it?

Ellis: It was Cyrk by Cate Le Bon. Do you know that record? But..for what it’s worth, they said no. [all laugh]

Matheny: Oh no! You should have explained your situation, told them you really needed it for your creative process..that you could just make it and they could throw it away, but…

Ellis: I sort of did. I was like “I am so totally obsessed with this record that I need to make a poster of it. I see she’s on tour all summer. Do you think we could make it work?†And they were like, “no.â€

Matheny: They were just trying to encourage you to get to your deadline.

Ellis: Yeah. They were like, “stop procrastinating.â€

Matheny: Seeing as how you have written this book for children about two very precocious, intelligent and quirky kids, could you each talk a little bit about the familial environments of your own childhoods? How your own imaginations might have been encouraged or shaped? For example, were you ornithologists, were you obsessed with animals? Did your parents surround you with books and forbid the television? Can you think of any details that might have shaped your creative worlds as children and spilled into the ways you each interact with the world around you creatively as adults?

Meloy: I don’t know. I grew up with parents that were very encouraging and supportive of creative pursuits. Even though my Dad had this thing that you should never do anything creatively as your main job. You should only ever do it on the side. Um, which is probably sensible. But thank God not everybody does that [laughs]. I think I was just surrounded by [people who] encouraged me to read and to write and to draw. And I think that kind of snowballed into what I do now. I wasn’t an ornithologist. I feel like a lot of the stuff in the book, certainly Prue, is based on Carson’s childhood experiences.

Ellis: Yeah, and I wasn’t really an ornithologist type. But I was a total reptiles and amphibians type. You know, just turning over logs and looking for salamanders and turtles and snakes. I had a room full of terrariums and I was always kind of catching things and keeping them captive. So I spent a ton of time in the woods doing that kind of stuff. And read a lot and drew a lot. My parents were hippie-types. They were really lax and certainly not negligent, but we were allowed to do whatever we wanted in terms of playing by ourselves in the woods from a young age. We weren’t super supervised. I don’t remember being supervised as a kid [laughs]. I feel like, even when I was my son’s age, and he is six, I was sort of tromping around in the woods by myself. And they just sort of trusted us to stay close and make our way back in time.