“Drinks With†is an interview series started in 2009 by Skip and Timshel Matheny, currently songwriters in the band Roman Candle. The interviews are almost always done in person and typically discuss the creative process.

Timshel met up with Joshua Ferris after his Parnassus reading at the Nashville Public Library. The two of them walked three blocks to The Hermitage Hotel where they were able to sit in the mostly empty dining room of the Capitol Grill, eat, and talk about writing, Amazon Prime, and the personal demands of the Internet.

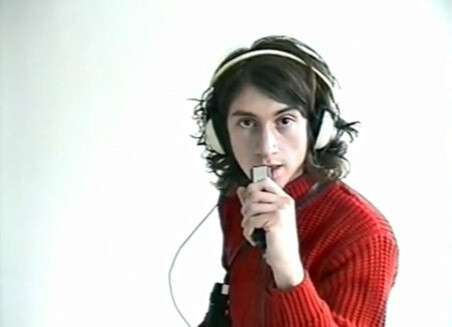

Timshel: Can you listen to music when you’re writing?

Josh: I actually do listen to one album. Juliana Barwick. It’s called The Magic Place?

Timshel:Â You listen to the same album every time?

Josh: Yeah, the same album. Not every time I write. But if I need it, I listen to that one album. It’s very ethereal.

Timshel: No words?

Josh: She is singing. It’s just very… I think it was recorded in a church. And it has a very ethereal feel. And it’s really a magical album. I think I have like 1100 plays on I tunes of that album. I have her second album but I got it on vinyl and I lost the download code and so it just sits on my shelf and I haven’t listened to it. You know, some albums I will buy and have every intention of listening to them and they will just sit on my shelf forever.

Timshel: Do you do that with books?

Josh: Of course. But that is more of a pathology. My book-buying is pathological. You know, I will never read Jack London. But then, all of a sudden, there I am buying Jack London. I mean who buys Jack London? You get that shit for free online. But I’ve got to have Jack London on the shelf. It doesn’t make any sense. It’s more like shoring up against barbarism, right? That’s how I feel about it.

Timshel: So you still buy actual books? You don’t read them on a Kindle or anything.

Josh: No. I don’t read [ebooks] at all.

Timshel: You never tried to?

Josh: I mean, yeah a little bit. Here and there. I mean before I stopped buying entirely from Amazon I’m sure I glanced at a Kindle.

Timshel: You stopped buying entirely from Amazon?

Josh: Yeah. For the same reason I stopped using Spotify. I mean this is the only power I have. And it ain’t changing the world, but I believe in it. So…

Timshel: Oh. No more Amazon Prime. Really? That’s going to hurt.

Josh: It does. You’re right. But, are you going to sell your soul or are you gonna get your Prime? (laughs)

Timshel: Do you think you would have even noticed if you hadn’t been writing books and trying to sell them?

Josh: Well then I would have just been some kind of douchebag investment banker making tons of money and I wouldn’t give a shit. Like, to re-conceive of me as a guy that’s not writing books is to re-conceive of me in all sorts of different directions. And so then, why not buy from Amazon. It’d probably be the least of my crimes (laughing).

Timshel: So were you always writing even back when you were working at the advertising agency.

Josh: Yeah. Probably.

Timshel: Did you think of your work in the advertising industry as something to just to pay the bills or was it interesting to you–were you kind of bi-vocational?

Josh: Oh no. That [advertising] was never real. I mean even when I was fresh out of college. I was a paralegal for the department of children and families in Florida. This is what my mom did. She wasn’t a paralegal-she was an actual investigator. And so I got the job and I would photocopy stories and just read them while I was supposed to be working. I mean I probably shouldn’t have (laughs) but that’s what I did.Â

So yeah, it was always sort of like, whatever I should have been ostensibly been doing it was always in the service of writing.

Timshel: So was your family pretty encouraging about writing as a career?

Josh: My Dad was extremely encouraging but practical. And so the two things kind of collided. But I think his overriding principal as a parent was to make possible things that would never have been possible for him. It took the form of something that he never really knew how to understand—he never understood Fiction or the appeal. But I think he saw it as representative of that which he never got himself. And so he encouraged it because it was an iteration of this freedom—economic freedom and freedom from your origins. I mean he was born poor and into a mean sort of world. And here he was sort of facilitating a different world for me.

And so he would always encourage me. He just didn’t understand it.

Timshel: How old were you when you published your first story?

Josh: My first story was published when I was 24. And it was a great boon but it didn’t change my life. But it just kind of gave me encouragement. And then I went to a program. And then after the program, a couple years afterwards I got my second story published. And with that I got my agent and so things sort of got pieced together from there.

Timshel: So you never had to reach that point in your ad job where you felt like you wanted to throw the towel in on writing? You know, where you thought , “Hey, this is a solid job with some benefits and this whole writing business, well…â€

Josh: No. My wife tells this story that whenever she would show up at the end of the day, she’d say, “Hey, how was your day?â€Â And we were just dating then- but I’d say, “One day closer to death.†Every time. And that’s just how it felt. It never felt meaningful.

I mean there were people that took great meaning from it. And I found it meaningful for them. I found it meaningful for people with kids whose lives really depended on that paycheck. And I found it meaningful for people whose creative spirit was really being fulfilled by the tasks at hand. They found it to be meaningful work. There is no disparaging that. And there is no belittling that. But my direction was elsewhere.

Timshel: You mentioned earlier tonight that you were reading Nabokov as a very young reader. Were your parents big readers? What kind of environment were you surrounded by that informed your early reading habits?

Josh: I remember asking my mom – we lived in Key West and we were at a drug store once and there was a spinning rack full of Hemingway. And I said, “Would I like this?†I was probably 11 or 12. And she was like ‘No. He’s boring.†And so I didn’t read Hemingway for another 3 or 4 years.

But I was intrigued. I wanted to know what was going on out there in the adult world. What were adults reading? What was it about this adult world? How did books inform it? So it was more about my curiosity about adults than it was about books. You know, the reason that I asked my 9th grade English teacher about Nabokov was because I heard his name mentioned in a Police song.

Timshel: Right, “Don’t Stand So Close to Me.â€

Josh: Yeah, that’s how it came my way. Just through pop culture.

Timshel: You have been writing professionally now for almost 14 years. You don’t have to work at the ad agency anymore. What does your writing practice look like at this stage?

Josh: Well, now the ever-present fear that we are going to go broke and have to get a job is palpable.

Timshel: (laughs) Is it?

Josh: Yeah, that fear, man? Yeah. Fear is a great motivator. If they took away my freedom after fourteen years of not having to answer to the man…I’d have a tough time with that.

Timshel: And now you have a family, a young son and a wife. How has this changed your daily habit, how you organize and spend your time, how you get things done?

Josh: I really think that there is some mystical law at work that says that the work needs to get done. Even though it is terribly cut and pasted together, it somehow gets done. Even though it doesn’t feel that way on a day-to-day. If it’s important work, if it’s important to you, if you’re determined to do it … I mean this is the whole mystery about how Alice Munro became Alice Munro, you know? Or how, almost any woman that also takes motherhood on and wants to write get’s anything done? The work has a way of willing itself into the world.

And this sounds mystical but I also think that if there is one thing that writing teaches anyone that spends anytime actually writing it’s to have an abiding faith—that the work will get realized. It is a reasonable faith. It’s a good faith to have. I really mean it when I say that it is a reasonable faith. An hour’s worth of work really will yield, sooner or later, an hour’s worth of dividend. I mean you may not feel that way during the day. You certainly may not feel that way the next day when you read over what you’ve written. But it kind of has a way, over time, of revealing itself. Or, if not revealing itself immediately, revealing what it could be. And you then pursue a different direction. And all the time that came before that seems like a waste was really just kind of tilling of the land. It just seems like really the most important thing that a writer can do is to develop that faith.Â

Timshel: It seems that often times in writing you have to kind of hover between doubt and faith, in order to be receptive, to listen, and then to actually complete the work. In so many ways doubt and faith are not opposite sides of the same coin but somehow work together.

Josh: Right. One does not negate the other. I mean if you’re a novelist and you sit down at one point in time, you’re going to have what you hope to be a finished book of 336 pages, right? None of it is written. What is that but an act of faith? The doubt can be utterly strangulating. It can be completely consuming. But unless you overcome it nothing is going to get written and the book isn’t going to be done. But [the doubt] is certainly going to be present for the lion’s share of the days with which you are trying to knock this project out.

So you have to learn how to be comfortable with doubt, self-doubt, skepticism, you’re own insufficiencies…all sorts of things. It’s just — you have to learn how to do it. And I think most people who eventually stop writing are those who don’t make peace with the overwhelming evidence that it makes no sense to keep doing it.

It’s those who fly in the face of what is really a very compelling argument- every day you wake up- to stop. And those who refuse that, or at least come to peace with it, or somehow find room for the possible and the impossible in the same moment in time—because really, finishing a novel looks like an impossible task when you are on page one. It’s impossible. But what is possible is nurturing it for that day. And you’ve got to come to peace with basically that contradiction that’s at the heart of the process.

I don’t know what essay it is from but Emerson has a quote where he says, “ The years teach much that the days never knew.†And that’s, you know, pretty good advice for a writer. The days matter. But the year is going to give you a better sense of what you can do than the day will.

Timshel: Earlier tonight I asked you for some of your secrets on how to work through doubt in the early stages of writing and you said, “Age helps.â€

Josh: Yeah.

Timshel: What were some of the ways that you have learned to quiet that voice in the process so that it did not hold such reign over your time and work?

Josh: I think there were little strategies along the way. Like, not reading back what you have written.Â

Timshel:Â During the entirety of the process ? Or just from the previous day?

Josh: Like what you wrote over the past week or so. Just not reading it for a while.  Because purity in the process is to not worry about product. And what are you doing but focusing on product when you’re re-reading? Just giving yourself a bit of time. So when you go back after waiting a bit and you read and you find something that doesn’t read like me in my bad mode self,– it almost sounds like somebody else wrote that– you can see so much clearer than you would have on the day you wrote it.

I mean the editor is always smarter than the writer. But the writer and the editor are always one and the same when they are reading back what has just been written. So the important ontological distinction between the writer and the editor is time. And time works wonders in terms of giving you the proper distance so that you might glimpse the possibility of something good coming out of your work. Not a parody. Not a cheap rip off. Not an honest attempt at someone else’s work. But something that has some authentic kernel of what you might have to say. Or it may just be a matter of phrasing. It may just be, “Oh I like that rhetoric. And it doesn’t sound like my old voice. It sounds like something that I’d like to read.â€Â And I think you can only do that by getting distance.

I think that it also helps to have really modest expectations.

Timshel: (Laughs)

Josh: Doesn’t it? If you only have the hour to accomplish anything, I mean what can you really expect of that hour?

And there needs to be some genuine self-respect. You need to bring genuine self-respect to bear for that hour if you’re doing it in an authentic and devoted way, no matter what. It could be complete shit. But there is real nobility in respecting that hour for its effort. And privileging the process over the product.

Timshel: How much does reading have to do with your process? Can you read at all while you are writing a novel or at some point do you have to stop reading? I know with making records there have been times when we literally have to stop listening to other music…

Josh: Right. I think I know now within about ten minutes of a working day when Virginia Woolf has colonized my mind. And I just stop. “Just stop sounding like Virginia Woolf and start sounding like yourself.†And Virginia Woolf is an odd example. It’s not often Virginia Woolf. But if I read somebody with a really strong voice — Pynchon or — it doesn’t take long for me to be like, “ I know what’s going on here. You’re being promiscuous with your voice. And it’s not working out.â€

I think before, when you are an apprentice writer you want to believe that all of the awesomeness of the writers that you love that make you want to be a writer is possible for you? So in other words you could absorb not only Pynchon but also Proust and also Joyce…like the Sky is the limit! And so I think that there is real merit in impersonating these people in order to try and figure out what you’re capable of.

But very quickly you learn that that’s not really possible. That is really only possible with bad books. You could assume all of the characteristics of all the bad books because they’re bad books for a reason. They’re probably bad because they’re rip-offs of something else. So it’s a useful period to go through. But then somewhere along the line, that kind of ‘trying on and taking off’ might get confused for what the final objective is. Which is to write like x, y, or z.

And that’s just death. That’s just an error.Â

So you do that for a while and then you recognize, “Hmm, that was a terrible phase.†And you struggle and you doubt and you maybe even put it down for a while. But ultimately if the work has to get out some way or another, whatever that work may be, it finds it’s way. And then you write something and it doesn’t sound like anybody else. And you’re not sure why. But you know that that is the thing you should be writing. Because it is some authentic expression of you’re imagination or your wisdom or whatever the case may be.

Timshel: I have heard you say about this particular book that you were kind of writing it in order to find out what you think about privacy. That often times you write to find out what you are actually thinking about things.Â

Josh: These things are so new—I mean the question of what does it mean to be a private person in the age of the Internet? I think that the only insight that I gained over the course of writing and thinking about it, that’s specific to identity and the Internet in particular, would be that a lot of people are worried about getting their identity stolen and having their bank accounts emptied. But the more pervasive fear on the Internet is that you’re missing out. That other people are actually living life in much more rich and interesting ways than you are. Which is another way of saying, “why won’t someone come along and steal my identity?†You know? It is disrespectful to your own identity to look on the Internet and see that everyone else is ‘winning’ and you’re ‘losing’. It’s a pervasive and understandable response to social media. But it is false, I think. You have to have a robust sense of self to resist that urge. And I think the Internet is basically asking for a more robust self.

I mean—it’s not. It’s basically just feeding our distraction from the terrible questions that lurk out there. But somehow it may also be just asking for a more robust self, on all counts — the amount you might be distractible, what matters — all sorts of things. The internet is asking you, it’s almost demanding that you become stronger in order to resist not only it’s allure but all of the snares that it presents with every click.

Timshel: Do you feel pressure to participate in social media?

Josh: I don’t feel pressure from anyone. Which is awesome.

Timshel: Right. Because to self-create a kind of “platform†is kind of the standard expectation now isn’t it?

Josh: Right. It is. And it’s probably very necessary. But, you know I’m not really sure why I write. Like it’s a compulsion, maybe a kind of pathology? But I did not start to write in order to sell books. And I did not start to write in order to relate to a non-existent and very nebulous audience. And now that I am writing books, and books that I like, and books that get published- I feel as if that is sufficient relation. It was always sufficient for me. I mean, the guys that I read when I was in college, for instance — there was no contacting them. Maybe they’d once conducted an interview that was published in some obscure journal that I would have to dig through microfiche and the stacks in the library to actually get an idea that they walked the earth. Now maybe that was a kind of unnecessary mythologizing of these human beings. But nevertheless it was about the work. It was a way in which it remained about the work on the page. And I think that’s still what’s most important.

And so I make myself available. We’re having a conversation now. I’m happy to talk to all sorts of people. And to come out and do book tours. And to do things that a lot of writer’s just dismissed who were publishing in the 60’s and the 70’s. And who had a certain scorn for the media machine—which I completely lack. I find it crucial to have these conversations. But I don’t find it crucial to respond to every tweet about me. That seems about the self. And everything that I do when I’m writing fiction is to transcend the self. The self’s mortality, the self’s limitations, the self’s squalid little ponds, you know– just get away from it. And I think that social media, all it does is bring me back to it. Because all I have to pedal on social media is my self. And that’s just not interesting.